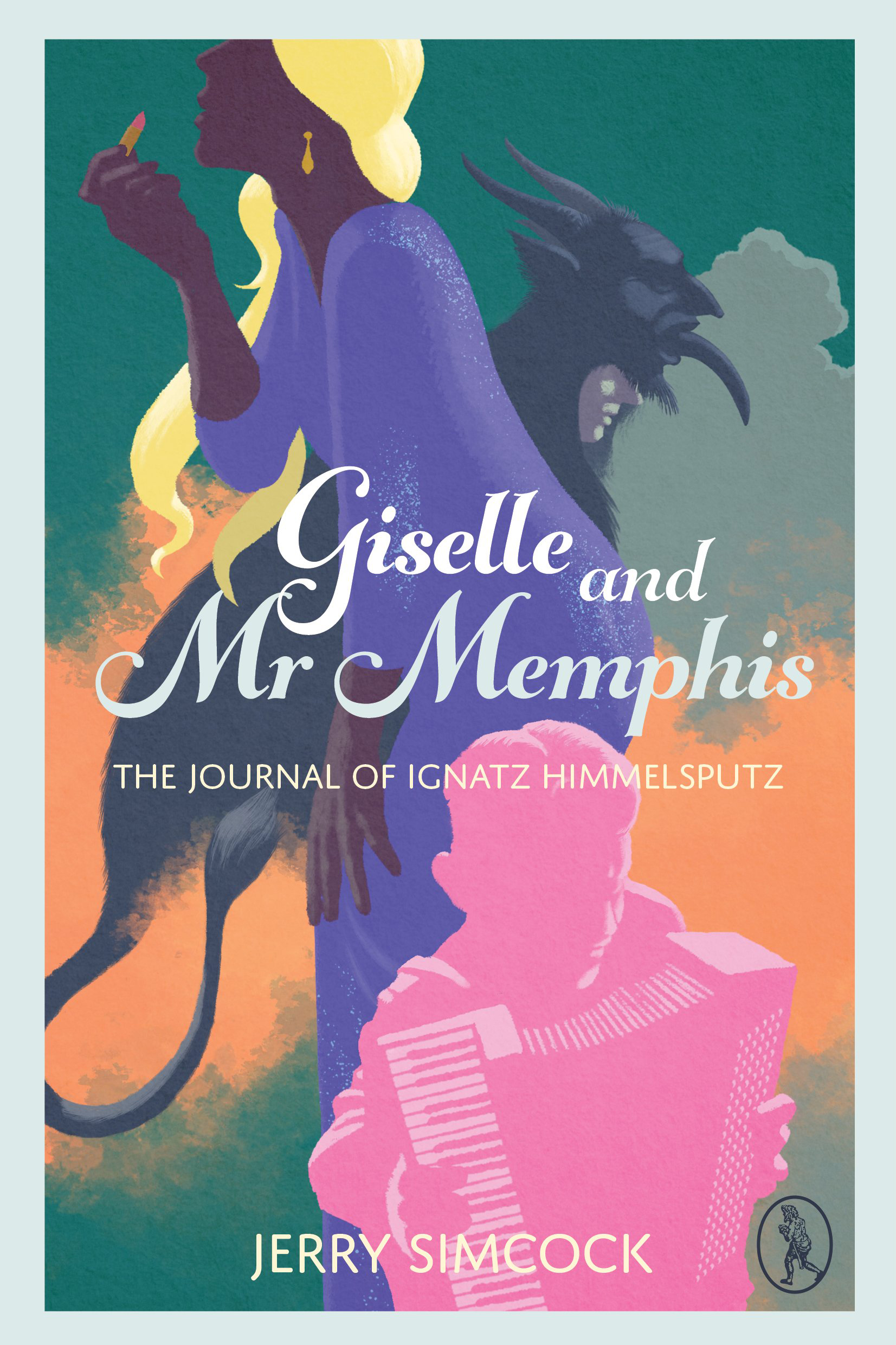

The Making of Giselle and Mr Memphis

It is time to get back to business as usual – at least for a bit! Rightly or wrongly, I have been distracted by the horrors of war, and now my responsibilities to our authors must recall me to my duties as a publisher. I can think of no better place to start than with Jerry Simcock’s excellent debut novel, Giselle and Mr Memphis. It is complex and also very topical. It too is about peace, tolerance and forgiveness, the triad or trinity we really need in a fragile world. Who better to explain its genesis than the author himself?

Allan Cameron, Pitigliano, April 2023

– – –

The making started way back in 1974. I say making because there was so much more involved than just writing. The writing started in Ray Ross’s Find Your Voice writing class in Edinburgh around the beginning of 2006. One of the first tasks Ray set us was to think up an imaginary friend – mine was Ignatz. At first he was just a wee man who could sit on my lap and whisper things in my ear, conjure up memories but over time he became a kind of timeless German dwarf figure, a bit brothers Grimm but more modern, someone of uncertain origin, Oskar from Gunther Grass’s Tin Drum was probably there somewhere in the background, but also a Turkish guy I had known in Frankfurt in the seventies, who played the guitar and only had a thumb on his right hand due to thalidomide. As he began to take shape he represented a mixture of folk I had met back then, who would sidle up to you in bars, a little drunk, but wanting to disclose how they had survived the Nazi period. He was not untarnished, traumatized, making the best of the now, a man who knew how to look after himself but was keeping the lid on the past, canny and a good story teller. I wanted him to emerge as if from a fairy tale – the book owes a nod to the brothers Grimm.

This imaginary friend took me back to Frankfurt 1973/4 where I had arrived at 18 fresh out of some bad A level results and a period grape picking in France. I’d been found a job in a bank where I was to develop my German and do some translation.

So what did this rather naïve, romantic, young man find? He is so distant from me now and yet, at times, feels close. He arrived one evening in Frankfurt Hauptbahnhof and entered a strange new world – his first period of truly independent living after school and family. The area around the station was full of GI’s, strip bars and prostitutes, he was offered dope, or a fix as he left the station. He had been to Germany before on an exchange to the Odenwaldschule, but this was different – he had to find his feet, make his own way.

He got set up in a one room lodging in Oppenheimer Straße – a bed a sink, a table and chair – kitchen and shower down the corridor. This place was basic with several floors of similar rooms and a stunning variety of tenants. There were folk from India, Canada, Honk Kong Africa, Ireland the US, English and Scots, there was a transvestite prostitute next door and he would try to sleep with the sounds of sex, laughter and tears as her pimp beat her up. There was Herr Drunk, with his missing legs, who begged on the Eisener Steg tapping out tunes on a cigarette tin. So many folk came drifting in, so many who offered friendship and a bit of support and influences, good and bad.

Perhaps what was of more influence on the book was the Balalaika – the bar over the street next to the Drei Königs Kirche – here was where the action was. It was run by a black woman, a jazz singer from New York, who was married to a German jazz composer. Much of the fictional Trompete is based on the Balalaika, certainly the music scenes – so many musicians and singers from all over the world rolled up there and played a tune or sang a song.

Once Ignatz was in my head, my memories of Frankfurt in the seventies flowed, the protests against the covering up of how many with Nazi pasts were still in positions of power and control, the demands for change, the American presence in the city – big cars with US plates, MP’s in uniform, Vietnam casualties. As a young student of history I had been horrified and affected by the uncovering of what had gone on the Nazi period, as well as all that was happening in Vietnam and had happened in the Biafran war – the horrors of slaughter and bombing, the inhumanity. I was talking to student protestors and aware of their determination to out and uncover the Nazi pasts of many who were in power. I had begun to question the stories of glorious derring-do that I had read in my early teens and was now more of a witness to the horrors of history.

At Sussex University a year later, studying European History and German, I researched the Nazi period, the ideologies, theories and the actions that underpinned Nazism and the mythical creation of the Master race. I studied Fascism and wrote a dissertation on the origins of Nazi ideology. All of this, my desire to understand how such ideologies can get a grip and lead to such horrors of selective mass killing, how acts of evil were justified in terms of maintaining ‘racial purity’, how some life was considered unworthy of living, continued to resonate with me throughout my life and led to me wanting to help and support others.

Writing in 2006/7 I added my own thoughts to all these memories, considerations and concerns about how easy it is for humans to slip into acts of ‘othering’ and then to harm others, how we are never that far away from an unkindness, an act of brutality, a massacre, how easy it is to slip into cruelty given the right conditions. There are, unfortunately, always examples of this whether sexual and physical abuse in children or care homes, grooming, or more deliberate racist attacks…we are never far from it, it seems to me.

Post University and a stint as a baker (baking also features in the book) I worked for many years with children and adults within schools, psychiatric settings or care situations. And not far from the back of my mind was how these were the people, who were ‘othered’ or hidden away, seen as too much of a burden, killed, during the Nazi period. I worked in a psychiatric hospital as a teacher. Parents were desperate for cures, or schools were keen that these difficult children were found a place elsewhere. I sometimes thought that we were not too far from Aktion T4 and that famous 1938 petition to Hitler from desperate parents asking for the mercy killing of their son, from considering others to be ‘Life Unworthy of Life’, not too far from eugenics. Whilst writing the early drafts of the book I worked for a local charitable trust who offered a space in wild woodland for folk with mental or physical health issues to work alongside volunteers and carers in woodland management activities. I cared for a young man with little speech and mobility problems, brain damaged at birth. He’d often attempt to harm himself and need soothing and containing, tasks together and sometimes I’d push him around in a barrow, sometimes help him deal with his frustrations, he was well cared for and medicated with so many people supporting him to enable him to live and find some of joys in life. Caring for him and the connection that developed between us had a huge influence on the novel, in particular Ignatz’s care for Lucy and his longing to return to the forest.

In the book I deliberately chose Giselle and Ignatz characters who were both mythical and other, who were outsiders. I wanted to investigate how they might have been damaged themselves, yet also be capable of harming others. I focussed in on passivity in the face of power, fear, group mind and how this can lead to taking it out on those who are considered other. How the Nazi ‘moment” pulled people along and did not allow or permit other views. How individuals get caught up in horrors through fear and intimidation, whether through looking away or taking active part in eradication.

But this novel also wanted to consider moments of joy, of coming together and of compassion, moments of bonding, music and song. The journey to evil is nuanced and complex and is built from hurt, despair, anger and ‘othering’ and in the steps along the way there are also moments that contain joy and kindness.

I hope this book will give people pause for thought and allow for a consideration of how easy it is to slip, to be pulled in a direction that leads to the horrors. And once those horrors have been suffered, felt, repeated, maybe broken free of by acts of redemption, how can you best deal with guilt and trauma – by keeping the lid firmly on those memories or by slipping it off and releasing the pressure? Ignatz chose to write it down, but parcelled his writings up and did not release them until he knew he’d soon be gone. Professor Doktor Bühler thought he had found a way to rebuild a life working or the good of others but, in the end, has to take another way out. Giselle, well, Giselle became Giselle. Herman, well, he was spared the full gruesome details for quite a while but will now have to live with the knowledge of what his father did…the knowledge he was always pushing for.